Across the globe, AI continues to push the boundaries of what we thought possible, including how we design our homes

Words Carrol Baker

Can you imagine AI designing your home? It might be one step closer than you think. After all, AI can write copy, optimise design layouts, build websites and predict future outcomes. Some AI chatbots can also mimic human interactions.

Stela Solar, director of the National AI Centre, CSIRO, says beyond the day-to-day things that AI can assist with, it’s playing a crucial role in solving some of the greatest challenges in Australia.

“This includes adapting to a changing climate, protecting unique ecosystems, accelerating drug design, and helping cities and towns run as efficiently as possible,” she says.

In the architectural sphere, some might argue that AI exists in the juncture between art and technology. Architect Dr Fiona Gray from Bioliving By Design says AI does feel like a natural continuation of that relationship.

“AI offers the ability to process and analyse large volumes of data far more efficiently than traditional methods,” she explains. “This makes it possible to explore multiple design scenarios quickly and run performance simulations related to things such as energy use, lighting, ventilation and thermal comfort.”

Breaking it down into nuts and bolts, AI can help with specific tasks, but not all. Architect Luke Carter from Sandbox Studio says in particular, AI can be effective with repetitive, mundane tasks. “This could be writing documents that are generic in nature, allowing us greater time to deal with intricacies,” he says.

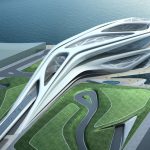

AI can boost creativity, streamline workflows, aid project management, and it can help homeowners to conceptually visualise what their completed home could look like. The very real potential of AI lies in its ability to optimise design processes, maximise efficiencies and reduce project timelines, which can lead to cost-saving outcomes.

James Loder, an architect from Wardle in Melbourne, says the speed of design process is a definite attribute. “It means we can more effectively and quickly communicate to a client,” he notes. Wardle began using AI tools before many other practices jumped onboard. “It’s a fantastic means of drawing upon a large suppository of information in a very efficient way,”

he shares.

James adds that while AI is useful, it requires a human mind to curate the outcome. “It won’t replace that aspect of critical thinking that we bring,” he says.

AI-powered design tools

In the past, architects would draw diagrams and plans by hand. That changed with the development and deployment of Computer-Aided Design (CAD), a tool to assist with detailed technical drawings. Fiona began her career as an architect with a drawing board.

“I’ve seen how computer-aided design revolutionised what we could imagine and build,” she says. “AI could take that evolution even further by suggesting new spatial ideas, forms, and design approaches that challenge our assumptions and expand our creative toolkit.”

One of the tools that James uses is ChatGPT, a generative artificial intelligence chatbot. “It helps with the speed of writing reports and distilling large amounts of information,” says James.

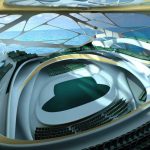

In design, AI can also implement image generation tools — a key one is Midjourney. “It supports a fast exploration of beautiful visual material and detailed character,” explains James. “We can test it as a conceptual narrative, create images that support an idea in an abstract form, or use it to enhance the visual representation of a prospective view.”

The technology continues to evolve at quantum speed, so designers need to think on their feet. James says in this current phase of AI, anything we know right now will change and evolve in months. “Our approach is to not take it too seriously, to be nimble and playful with the way we are testing and exploring these tools,” he says.

It’s a slow burn

According to the RIBA Artificial Intelligence Report 2024, in the UK, 41 per cent of architects implement AI in visualisation, environmental exploration and idea generation. How does Australia shape up? The Australian Institute of Architects self-reporting survey results from September 2024 showed more than half of those who responded were using or exploring AI for concept design and renders, and design development.

The report showed some concerns with, among other things, the future role of the architect, liability when AI gets it wrong, loss of skills and knowledge, and unrealistic expectations of clients who have used AI to generate an “ideal home” engagement with the communities we serve,” she explains.

James adds that some of the benefits of AI in architecture are surprising. “You can generate outcomes that are unexpected. AI can push and test our thinking and there’s an immense benefit to that.”

Supporting sustainability

Informed and innovative designers continue to deliver sustainable designs in response to the fragility and finite nature of some resources, and to provide healthier, better-designed homes. James says AI could offer sustainability benefits in the operational performance of a building, particularly the embodied carbon. “Enormous amounts of data could be effectively synthesised or managed through an AI tool,” he notes. “This could be used to analyse building models and provide immediate feedback on potential ways to reduce embodied carbon.”

AI could potentially be a game changer with energy-efficient insights and optimisation of resources. Fiona says it’s also important to recognise the environmental cost of AI itself. “Training and running large models require significant energy,” says Fiona, “so we need to be selective and purposeful in how we use it, making sure its benefits to sustainability outweigh its footprint.”

The limitations of AI

AI is not an exact science; it does need to be treated with some degree of caution. James says it’s vital when using AI to double-check AI outputs, making sure the information is accurate. “It can make mistakes, and sometimes it can make things up in trying to provide what you want, which is disconcerting,” he admits.

James says AI is currently used like an automative tool, based on probability when information is fed into it. “I liken it to setting a design task with five architecture graduates. I’d select the one I like the direction of, provide feedback, and continue that exploration with a team member,” he says.

Another issue flagged with AI is a potential lack of new ideas and innovation. This is essential to improving practices, creating more efficient modalities and ways of accomplishing tasks. James says the risk long term with AI is that you aren’t progressing with new critical thinking. “AI is recycling content that exists elsewhere,” he says. “That would be a long-term risk if everyone shifted their reliance to AI. There would be nothing new.”

If information through AI is sourced from various programs, that raises another question: who actually owns it? Fiona says there are practical and ethical concerns such as copyright and intellectual property as AI tools are trained on vast amounts of material, much of it sourced without clear attribution. “This raises important questions about ownership of ideas generated by AI and whether they unintentionally reproduce or draw from copyrighted work without permission,” she explains.

One of Fiona’s concerns goes to the very heart of what residential architecture is all about — designing and developing unique spaces for people. “It’s about creating spaces with depth, soul and meaning. A human designer brings an embodied understanding of place that no dataset can replicate,” she reflects.

“The feeling of a gentle breeze, the scent of surrounding vegetation, or the distinct soundscape of a particular location are all sensory experiences that can only be grasped by being physically present and attuned to the environment.”

The spaces that designers create shape our lives and the way we interact with our environment at home. Architecture is human centred by design. It’s about fulfilling human needs.

Luke says that while AI might be able to potentially produce 80 per cent of the grunt work that architects currently do, it can’t do it all. “The remaining 20 per cent needs to be done by architects. Our social skills of communicating on a human-to-human level is what makes a project ultimately successful,” he points out.

Designing someone’s home is a close and personal collaboration between client and architect. It’s getting to know the individual and developing a relationship of respect and trust. Luke says the human-centred approach could never be fully replicated by AI. “For example, we have learnt through experience when clients don’t mean what they say, and what they mean when they say little,” he says. “This tacit knowledge will be the key reason why we think our profession will remain irreplaceable.”

The future of AI

AI is here. Of that fact, there is no doubt. The role of AI technology isn’t about replacing human creativity — it sets out to support and enhance it. AI and architecture can coexist. AI can efficiently do repetitive tasks and streamline workflows, with humans providing the necessary checks and balances. This means AI will enable architects to focus on the human-centred aspects of design — the imagining and the creating — so we can live in well-designed homes that enhance liveability into the future.

This article was originally published in Grand Designs Australia 14.2.